Business Opportunities and Crime Prevention

First the good news: crime has been declining for well over a decade in most advanced western democracies.

Now the bad news: we aren’t really sure why, although recent research is pointing in the direction of increased security when we are talking about burglary, car crime, theft – the ‘bulk’ or volume crimes. Violence too is going down but Internet-related crime, mobile phone theft and some of the more technologically based offences are on the increase. These often require a level of expertise that is beyond many of the opportunistic offenders that have been deterred by the increased security of cars, homes and commercial premises; so there is hopefully a ‘ceiling’ on the extent of their increase. We’ll see.

In this short article I’d like to talk about the implications of these reductions for the private security industry, and suggest that they offer new business opportunities not only in the UK but elsewhere. But it might require some familiarity with research (as an academic I would say that, wouldn’t I!).

The government’s approach to crime prevention

In the UK our best guess is that the declines in crime have been supported by a change in the approach of the Government to crime control. The Crime and Disorder Act (1997), brought in by the first Labour Government, was central to encouraging the police, local authorities and other local agencies to work together and develop a strategic approach to crime reduction at the community level. The starting point was crime data – analyse it, see what the problem is and then work out how to make it go down. There is much more to this than security patrols or CCTV cameras. We know, for example, that there are five main ways to reduce crime – increase the effort, increase the risk, reduce the rewards, reduce provocation and remove excuses.

Increasing effort might involve the typical locks and bolts with which we are all familiar and increasing risk may call for improved surveillance through CCTV cameras. Retailers hope that putting dye on high value clothes, or ink on stolen bank notes will reduce the rewards of theft. Controlling the taxi queues at busy periods when night clubs close should reduce provocation as should controlled service in pubs and bars. Similarly, well-trained door staff are not provocative in their handing of customers – they get better behaviour in other ways. Removing excuses, on the other hand, is perhaps a little more subtle. We all try to excuse our behaviour if we have behaved badly – think back to the last time you did something you shouldn’t have done!

The impact of removing excuses on crime prevention

Removing excuses is intended to make that process a bit more difficult. So, for example, when you go to one of those nice hotels that provide bath robes, and there is a discrete notice attached saying that if you would like to buy one you can do so at reception, the hotel management is saying ‘the bath robe is not like the tea and shampoo – don’t steal it!’ – your excuse has been removed.

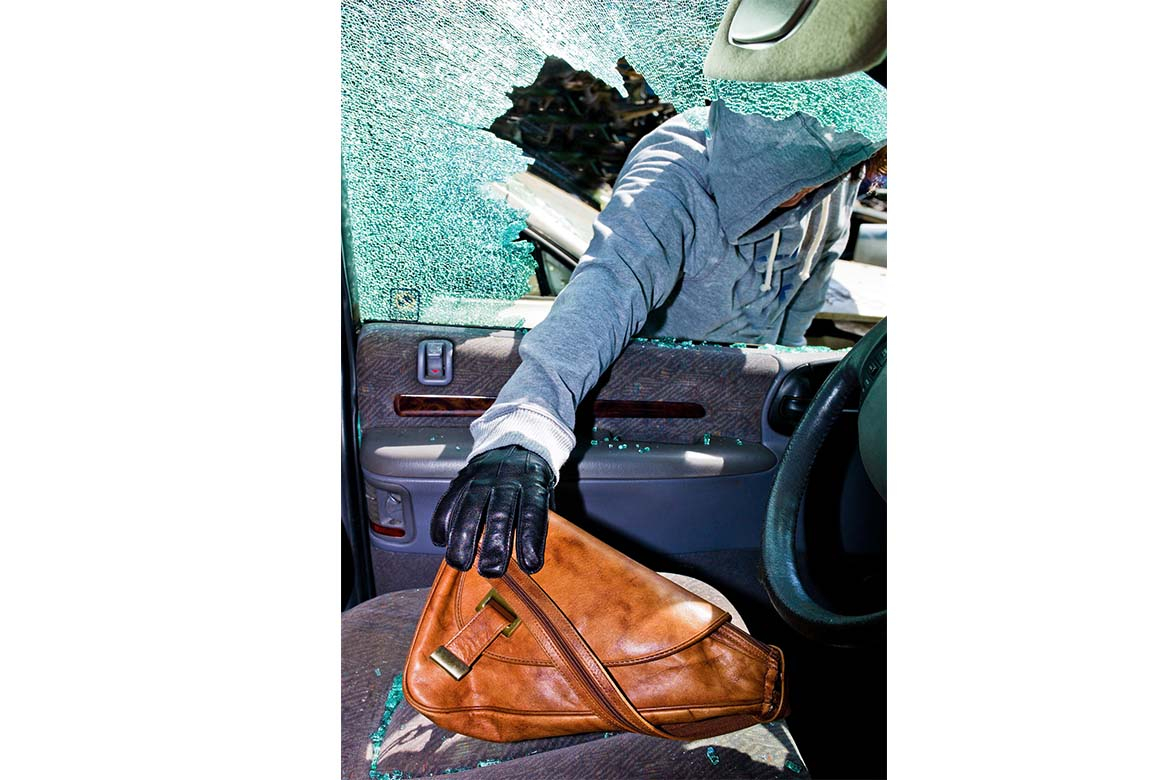

Let’s look at car crime as a more detailed example. In the late 1980s the UK had the highest rate of car crime in Europe. It accounted for 25% of all UK crime. It was everywhere. There were nightly news items of young men stealing cars and joy riding around the roads, doing wheelie turns and having a great time. Something had to be done and despite repeated requests to the motor manufacturers to fit deadlocks and immobilisers at the point of manufacture, nothing much happened.

Then the Home Office published the car theft index. This ranked cars by car type against the chances of being stolen in one of three risk bands. None of the manufacturers wanted to be at the top of that list – and the Home Secretary at the time told them that the next issue of the index would name and shame the worst manufacturer. Off they went and built in car security in the factory. They had effectively been shamed into it – the risk of being at the top of the list was high for some manufacturers and the excuse ‘we didn’t know we had a problem’ had been removed.

Over the following 10 years or so, from the early 1990s car crime started to fall and is now around 70% less than it was in the late 80s, as the chart above shows. And this is not because sentences became tougher, or more thieves were caught, or cars became cheaper, but is simply because the manufacturers took their responsibilities seriously to help protect their customers against crime.

What has all this to do with the private security companies?

The approach that helped to reduce car crime has also helped to reduce other offences. As the Crime and Disorder Act recommends, it begins with analysis of the crime data and a thorough understanding of the offence problem. But it is likely to fall into disuse not because it has failed as a policy but because the necessary skills to deliver it are no longer likely to be available to the police or local agencies. The cuts begin with civilian staff and many of these are analysts – the very people who can analyse the data and provide suggestions for prevention. There is a growing gap that could be filled; and in many countries overseas the expertise did not exist in the first place but there is a desire to develop the approach, so another opportunity to provide a service.

This approach is not restricted to the provision of services to others; it also applies to the ways in which the private security industry runs its own business. Cash carrying, manned guarding and the provision of door staff and surveillance systems might all be improved, at reduced cost, if crime problems were better understood. Crime is heavily ‘patterned’ in the way it is manifest – so we get crime hot spots for example, but we also get repeat victims.

One study showed that by eliminating all repeat bank robberies (where the same bank was robbed more than once in a year) the rate of bank robbery could be reduced by 35%. Similarly, burglary on a very high crime housing estate was reduced by 70% simply by protecting first time victims and ensuring that they were not victimised again.

Knowing which crime prevention methods to implement

Understanding the nature of offending in the area of operation can assist companies in improving their services to customers and also in providing that improved service at reduce cost. If we look at a specific example of cash in transit robberies, which rose significantly around 2007, this was caused by an increase in offending in the London area, not across the country. The preventive effort, which as it happens was extremely expensive, could, therefore, have been focussed on the problem rather than offered at great expense everywhere. The Association of Chiefs Police Officers, for example, issued guidance to all forces on how to deal with cash carriers and cash and valuables in transit losses, despite the fact that the vast majority of forces did not have a problem. It compares with ACPO providing guidance to the Met on how to deal with sheep stealing because it is a major issue in Dyfed Powys! They wouldn’t do it.

So understanding the nature of the problem in some detail, and in particular where it is and how it manifests itself, can help to tailor responses to the particular problem, focus the resources and assess the effect, which can then be modified if it is ineffective. It is common sense – but, sadly, common sense is not that common.

Gloria Laycock, OBE

Professor of Crime Science University College London