This way out…

“Safety is not an intellectual exercise to keep us in work. It is a matter of life and death. It is the sum of our contributions to safety management that determines whether the people we work with live or die.” Sir Brian Appleton after Piper Alpha.

We all have had this shared experience:

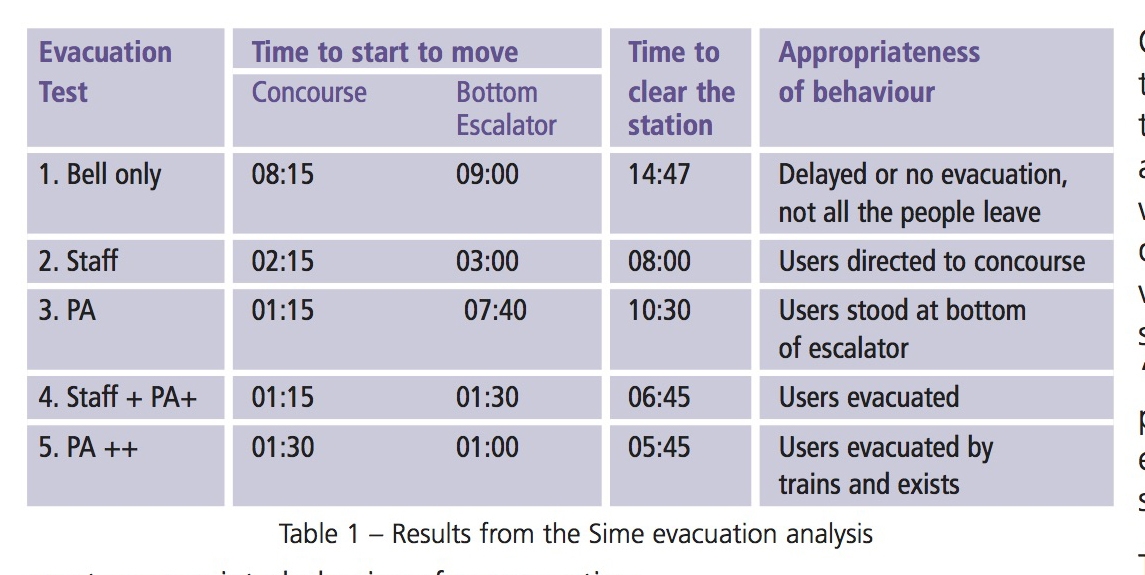

An alarm bell rings… and we ignore it. Over 20 years ago, Sime outlined how people react to various types of alarms (see the table below) yet we still work on a series of misconceptions relating to human behaviour during emergencies. Evacuation is a two-stage process consisting of the initial “reaction time” and then the actual “evacuation time”.

The former of these is the time it takes the crowd to start to move, which is the human response to the different types of alarm signals: bell only, staff (such as fire marshals), Public Address (PA) announcements and combinations of these.

The table highlights the time to start to move and the time to clear the station from the Sime experiment.

The combination of marshalling plus appropriate and informative information on the PA system provided the quickest and most appropriate behaviour for evacuation (1 minute 15 seconds, compared to 8 minutes 15 seconds for an alarm bell only, and users evacuated via the most appropriate exits).

For compliance with the various building control regulations and guidance, the “evacuation time”, namely the travel distance to the nearest exit, the egress capacity, etc., is the criterion for occupancy. However, if the building occupants take time to start to move then the evacuation time will be a function of both the reaction time and the travel distance/egress capacity. As we can see from the table above, the nature of the alarm can stimulate much faster responses, this in turn can save lives, yet this process is often ignored.

Behavioural based safety

Sime’s work was published over 20 years ago, yet it is still overlooked in the design of places of public assembly. The assumption that people will not leave as soon as an alarm sounds needs to be factored into the building or event management system. Additionally, there should be careful consideration about the nature of the information provided in the alarm system. For example, if there is a security alert such as a suspect package found near one of the main entry/exit points – how does the alarm system inform the occupants of the direction of egress? How does the system direct the occupants away from the potential threat?

Over the last two decades of teaching/training around the world, we always ask this question of the venue security/ safety managers: “What is the procedure in the event of finding a suspect package?”

The answers (bar one) are always the same; “We sound the fire alarm!”

From this we may conclude that: Most people may ignore a fire alarm.

There is no directional information in the fire alarm – could this drive people towards the threat?

It may be worth spending time reviewing the alarm signals and procedures in your building or at your event, specifically the issue of getting people to start to move and how you inform them of the best, safest exit route.

Exit choice

An interesting experiment we run is based on Ellsberg’s Paradox. This is a paradox of choice and highlights the issue of direction from a decision-making perspective. We offer a £10,000 wager on a red ball/black ball outcome. We will give you £10,000 if you choose a red ball, but you must give us £10,000 if you pick a black ball. There are two choices, bucket 1 and bucket 2. Bucket 1 has 500 red balls and 500 black balls. Bucket 2 has an unknown mix, we do not know the mix, 90:10, 70:30, 40:60, anything is possible. You are asked to choose a bucket.

Most people will choose bucket 1, the known percentage. The odds of picking a red ball are the same in either bucket (anything is possible) but the rational choice is biased towards perception of lower risk. The probability is 50:50 in bucket 1. It feels like this is a lesser risk. Why this experiment is so important in the context of emergency behaviour is that, during an emergency, we make a choice of exit route. This choice will be based on what we know. We know the route into the building/venue. We may have never used the emergency exits. We do not know if they are locked, or where they lead, we do not know if that route is safer. This is Ellsberg’s Paradox in a different form. In an emergency, it is not £10,000 at stake; it is your life.

Summary

If you are a building controller, a safety officer, involved in emergency evacuation process or procedures, an employee or visiting a site/venue, ask the same question we do – what is the procedure in the event of an emergency? Then check the options for evacuation; it may only take a few minutes but it could save your life.

Prof. Dr. G. Keith Still FIMA FICPEM

Email: GKStill@me.com